Reflections on Games, Elitism, and Five Years of Work

Today, 4.20 marks five years since I began working full-time after graduation. Work and I are like the sea and the stone along the shore: with waves reshaping my edges in every moment, I've simultaneously become more aware of the contours of my self. After five years of this continual process, the person I am today is no longer the same person I was back then, to put it in the lightest way possible. This transformation is neutral, but I must acknowledge and appreciate the profound changes work has brought. Thanks to my job, I literally go places: I currently live in a country that barely crossed my mind five years ago. My work has pushed me, for the first time, to actively choose to open myself up, and thanks to this, I was able to connect with numerous people and join a network far outside of my comfort zone.

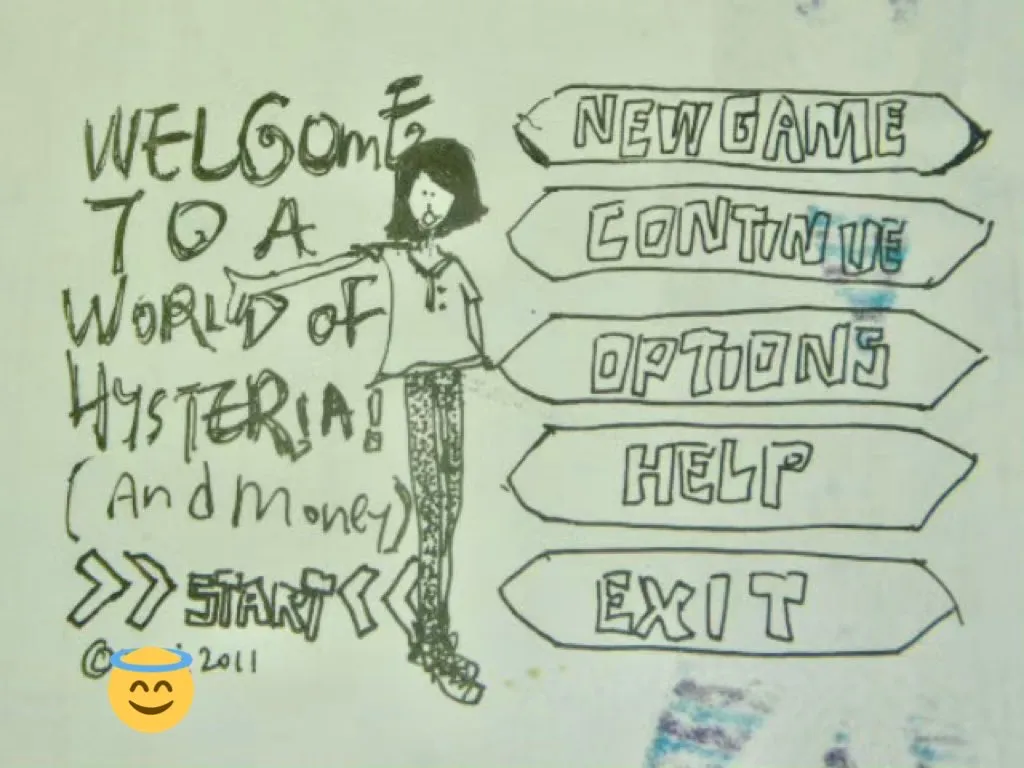

Doodle from 2011, Shanghai

Doodle from 2011, Shanghai

For those 5 years, I've always been in the games industry. The longer I am in this industry, the more strongly I understand games’ special place in contemporary culture. (I’m tempted even to use the word "civilization," though it’s not my place to pull a Johan Huizinga.) The broad concept of games has existed since the birth of human civilization and has always been independent of productive labour. In a narrower sense, games remain one of the few forms of entertainment, culture, and media that belong to virtually everyone. Games have no obvious “gates”; there are almost no geographical, spatial, or material barriers to the act of playing games. People from different countries are mostly on the same page when it comes to gaming culture and games of the moment. While there are undeniable regional differences in the games people play and enjoy (for instance, Sultan’s Game is literally shifting culture in China right now, but the English-speaking world is largely oblivious), there are numerous games that are universally recognized and appreciated, with people sharing similar interpretations and knowledge of these games globally.

Nobody is actively producing discourses to segregate and divide games (although a lot of people are producing discourses about games to segregate and divide people). While there are non-game things that are packaged and branded as games, games themselves are rarely branded as something else. There's no absolute authority in games. No one makes a game with the main purpose of competing for the recognition of an award or jury. Games made by well-known, wealthy, well-staffed, and prestigious teams sometimes do worse than those made by one anonymous 20-year-old furry who spends a few hours a day in game dev after class. There’s also no singular criterion for critiquing games. Everything becomes transparent and self-evident through the very act of "play."

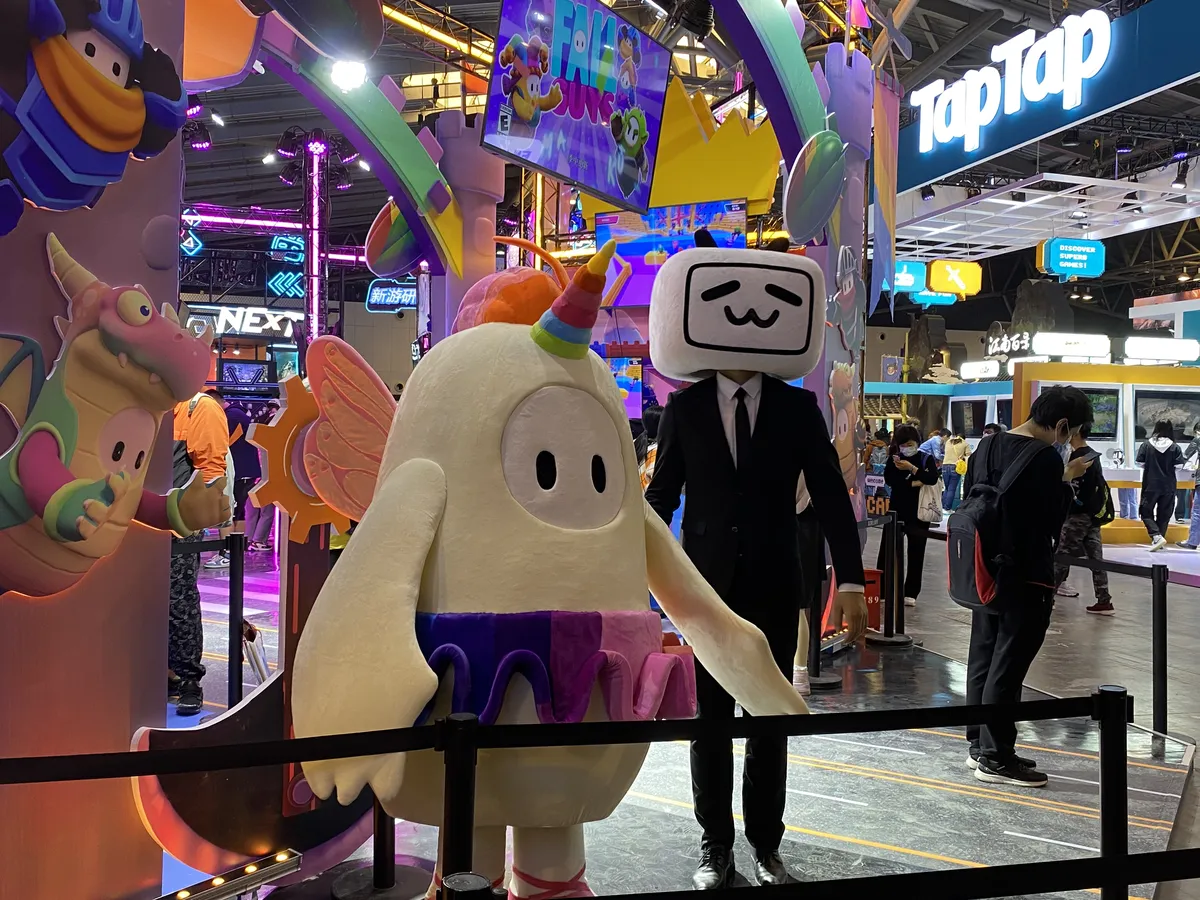

My first gaming convention: WePlay Expo, Shanghai, 2020

My first gaming convention: WePlay Expo, Shanghai, 2020

If I were to summarize what I mean briefly: games heal all forms of elitism. To some extent, my experience in this industry has made me increasingly sensitive and resistant to elitist and meritocratic narratives elsewhere in life. Particularly in mainstream Chinese society, playing games as a non-child has always carried negative connotations, often linked with addiction, lack of self-control, or seen as unproductive or branded as 不务正业.

Because games are fundamentally non-elitist, working in the game industry has been and will continue to be humbling. As a product, games couldn’t be more direct-to-consumer, yet selling the product or earning revenue from the product is never the end point. The unique interactivity between makers and players makes it so that games and people are constantly in the process of reshaping each other. This dynamic doesn’t stop upon a game's purchase: as long as people continue to play, the tension remains. The diversity and complexity of people make games endlessly difficult to fully comprehend. Many industry people seek data and charts to grasp the "game-player" relationship. While numbers do provide certainty and a sense of security, they represent perhaps the least vibrant aspect of this connection. As a matter of fact, the eternally changing and unquantifiable nature of the "game-player" relationship is what fascinates me most. Perhaps the desire to understand, to find a universal law or formula, arises from humanity’s instinctive aversion to all uncertainty. Despite spending five consecutive years in this industry, I regularly remind myself to stay humble and to seek answers through embodied play.

Digital Dragons 2023, Krakow

Digital Dragons 2023, Krakow

The "funniest" part about the game industry is that it's perpetually oriented toward the future, yet it can never promise a future to anyone within it. Layoffs, cancelled projects, and studio closures have been haunting me directly or indirectly for as long as I have worked. Although I don't want to pessimistically suggest that anyone who stays long enough in this industry will inevitably encounter such circumstances, my experience makes it difficult to believe otherwise. As people forming the foundation of this industry, we should not rationalize or normalize these things just because they happen frequently.

On a personal level, five years is a very abstract concept for me to grasp. Just as five years ago today, the nervous “baby me” finding her place in a Shanghai office could never have imagined I'd one day be writing these words from a bench in Amsterdam's Oosterpark. Today, I likewise can't foresee where I'll be in another five years: whether I'll still be in this industry or in what form my work will look like. Let me conclude with a quote from Plato’s Laws, which I read in Byung-Chul Han's The Burnout Society:

"Human beings are created as the playthings of the gods, and that is really the best thing about them. Every man and woman should live accordingly, and spend life in playing the noblest of games."

My view in Oosterpark while writing these words, Amsterdam, 2025

My view in Oosterpark while writing these words, Amsterdam, 2025